I haven't looked at Mee's entry yet but am sure it will be fulsome, so I will be brief. Holy Cross & St Lawrence, which I visited yesterday, is one of most complete Norman churches that I've seen outside of cathedrals and, as well as a wealth of fittings, it contains a very good Doom.

I know I use superlatives, or is it hyperbole, too much in this blog but in this case the use of the word extraordinary is not an exaggeration.

PEVSNER.

Mee does not disappoint:

WALTHAM ABBEY. Every Scout knows it, for here is Gilwell Park, the 70 acres in which Scoutmasters are trained; and every English boy should know it, for it has sometimes been called Harold’s Town, because the last of the Saxon kings founded a church and was long believed to have been buried here.

In a field at the back of the church is a primitive bridge with a single arch which the boys call Harold’s Bridge, though it is younger than it looks, being only 600 years old. Of the old monastic buildings of the Normans there is little to see except a vaulted passage; there is also a 14th century gateway. The 15th century inn has an overhanging storey making a lychgate into the churchyard, and a shop in the market square has timbers carved by medieval artists showing a crouching woman with a jug and a man with his tongue out. There are many 16th century buildings in the town, and a square near the abbey is still known as Romeland because the rents from its houses supplied the papal dues. It was in a long-fronted house of this square that the seed was sown of one of the decisive movements of the world, for in it Cranmer met Bishop Gardiner on that day when he "struck the keynote of the Reformation and claimed for the Word of God that supremacy which had been usurped by the popes for centuries." It was a hundred years after this that Thomas Fuller was vicar here, and he never ceased to be proud because Waltham itself "gave Rome the first deadly blow in England."

One more link with the Reformation Waltham has, for behind an ivied wall in Sewardstone Street we may see a 16th century chimney of a house which has in it the walls within which John Foxe wrote his immortal book of martyrs, the poignant story of hundreds of the bravest men and women ever living in these islands, who walked into the fire to be burned rather than surrender their faith in God.

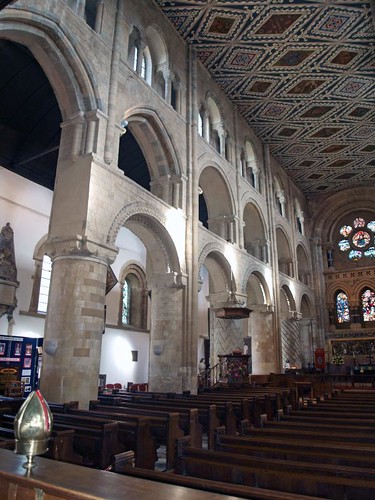

But it is, of course, the church and the cross that the traveller comes to see. They stand a mile or so apart, the church a fragment of its former self but without an equal in the county. It has the noblest Norman nave in the south of England. One arch of the great Norman tower remains, having been filled in to form the east wall, and standing at the east end of the churchyard we may see the herring-bone masonry of the transept wall which Harold must have seen; it has a blocked up Norman window above it. The south doorway is magnificent with the rich carving of a Norman craftsman. When King John signed the Charter at Runnymede there was rising here a church as long as Norwich Cathedral, being built as part of the penance John’s father performed after the murder of Becket. Waltham Abbey was one of the three monasteries Henry the Second then founded, and it has only been realised in our time how magnificently he carried out his vow. For on this abbey alone he spent over £1000, a huge sum in his time, when a labourer’s wage was a penny a day. The spade has revealed that Henry’s church was at least 400 feet long, and had two central towers linked by a nave as long as the nave still standing. Beyond the eastern tower stood the choir before whose high altar it was long believed that Harold’s body lay. Each tower had its transepts, those next to the choir being 140 feet across.

The ten acres under which the foundations of this great church and many monastic buildings lie were market gardens until a few years ago, when they were bought and divided between the Office of Works and the church authorities, who have laid out five acres as a Garden of Rest. Fragments from forest and mine far across England must lie below this quiet plot, for national records have been searched and we know the story of the stupendous task the repentant king put in hand. In the roofs 265 cartloads of lead were used, brought from the Peak and the Pennines to Boston and to Yorkshire ports, and thence by sea to London, where it was shipped on to the River Lea. The timber came, not from Epping Forest hard by, but from Brimpsfield in Gloucestershire and Bromley in Kent. We learn that William of Gant was the builder, and first abbot of the new foundation. Waltham Abbey remained the pride of our kings for three centuries, and even Henry the Eighth must have felt some reluctance about spoiling it, for he left it to the last. Then the vast building became a quarry for all, the only glory left being the western nave, which was used as the parish church.

We approach this great place through a deeply recessed doorway 600 years old, which was refashioned when the west tower was rebuilt in 1558, and we pass in through another beautiful 14th century doorway which was the west entrance to the abbey. It has vaulting rising from beautiful capitals, a running pattern of flowers, and carved niches on both sides. If we come at service time we shall hear the bells in the tower which inspired Tennyson to write his famous New Year verses, "Ring out the old, Ring in the new." He was living at High Beech close by when he heard the bells of Waltham Abbey and sat down to write these stanzas of In Memoriam:

The time draws near the birth of Christ;

The moon is hid, the night is still;

A single church below the hill

Is pealing, folded in the mist;

and then these more familiar verses of Old and New Year:

Ring out old shapes of foul disease;

Ring out the narrowing lust of gold;

Ring out the thousand wars of old,

Ring in the thousand years of peace.

Ring in the valiant man and free,

The larger heart, the kindlier hand;

Ring out the darkness of the land,

Ring in the Christ that is to be.

A place of great splendour is the nave, its Norman pillars impressing the eye with equal grace and strength. Above them runs the triforium, and above that the clerestory, with its array of columns supporting the round arches through which the light floods in. So thick is the wall up there that a vaulted passage runs through it all the way. All these arches are adorned with zigzag and some of the columns have zigzag and spirals cut into them, once filled with gilt metal, as we see from the rivets still here. All this great work is Norman except for a few piers at the west end, where the 14th century architects adapted the Norman work to their pointed style.

Columns fifty feet high run up to the ceiling of this wondrous nave, and we are brought at once from the 12th century to the 20th, for the painted roof is a mass of colour by one of our own famous artists, and the light by which we see it comes in through Burne-Jones windows. On the ceiling are painted the signs of the Zodiac, the labours of the months, and other symbolical subjects, all the work of Sir Edward Poynter before his days of fame - and the roof is lit by a rose window below which are three windows designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones before fame came to him. The rose window shows Creation, and below is a Jesse Tree with the patriarchs on one side and the prophets on the other.

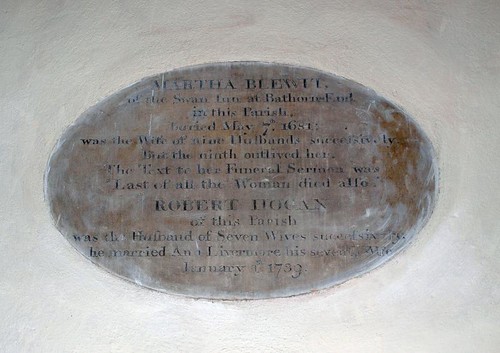

The oldest tomb here is the imposing wall-monument of Sir Edward Denny, resting on a shelf in his armour, with his wife in her Elizabethan ruff and hood below him, and their six sons and four daughters round the tomb; the last little girl is holding her sister’s arm. Standing by the wall is the alabaster figure of Lady Elizabeth Greville, cousin of Lady Jane Grey. Two 16th century families are in brass, Edward Stacey with his wife and son, and Thomas Colt with his wife and their ten children. On a realistic altar tomb of white marble is a sculptured panel of a ship at sea and mourning angels with tears on their cheeks; the tomb is to Captain Robert Smith of 1697, but resting on it is a bust of Henry Wollaston, a 17th century magistrate in Roman dress.

Out of an aisle we mount up to a beautiful chapel 600 years old; it has a crypt beneath it with fine vaulting. The chapel is lit by great windows with exquisite tracery, and has low stone seats round the walls divided by stone columns. It may be reached from outside through a beautiful doorway carved with flowers, and is charming without and within. Two of its windows have in them the Archangel

Gabriel bringing the good news to the Madonna, and three lovely figures at the Presentation in the Temple, one of the windows being in memory of Francis Johnson, who was curate and vicar 56 years. Above the altar are scenes at least 500 years older, a 14th century painting of Judgment Day: Christ is seated in majesty with outstretched hands, and Peter stands with other figures in front of a group of medieval buildings, while on the other side are angels receiving the good and the fires of hell receiving the wicked.

In this chapel are such memories of old Waltham as the stocks and whipping-post and pillory, the works of a clock which ran in this church for 260 years, a portrait of Thomas Tallis who was organist in the last days of the abbey, two Jacobean chairs, Roman remains, and casts of the abbey seals. Two other odd things we found in this museum; one a 16th century waterspout wrongly claiming to be part of Harold’s tomb, the other a grim relic of the days when suicides were buried at the crossroads, for it is a stake which was found piercing the skeleton of a man buried there.

Such is Waltham Abbey as we see it. It lives in history and in legend, for legend tells us of one Tovi, standard-bearer to Canute, who found a piece of the Holy Cross at Montacute in Somerset and built a church here to preserve it; to this day this Waltham church is dedicated to St Lawrence and the Holy Cross. It was given its name in the presence of Edward the Confessor, who was here in 1060. Here on its way to Westminster Abbey rested the body of Queen Eleanor for one night, and 17 years after lay the body of her King Edward, waiting in this abbey for three months during the preparations for his funeral at Westminster.

It is in memory of Queen Eleanor’s last ride that Waltham Cross was built. It is perhaps the best of all the crosses that bear her name, and was set up to mark the place where the body of the queen rested on that sad procession from the Notts village in which she died to Westminster Abbey where she lies. Twelve crosses were set up to mark her resting-places, the first at Lincoln, the last at Charing, and this, the one outside Northampton and a third at Geddington, are the only remains.

Waltham Cross stands actually in Hertfordshire where the road from the abbey joins the Roman Ermine Street, at the spot where the abbot and his monks met the sad procession from St Albans on a dark December day in 1290. Today it is in a busy street ; then it stood with nothing but a chantry and a wayside inn to keep it company. Of the chantry not a stone remains, but the inn is still close by; it was probably the abbey guest house, and has as its sign four swans which recall the swans on King Harold’s shield at Hastings.

It is believed that this cross was designed by William Torel, the goldsmith who made Queen Eleanor’s tomb in the Abbey. Much of his cross has survived the ages, though it has been twice refashioned from his materials. It has six sides and three tiers all richly adorned. The lower tier is solid, and each of its six faces is decorated like a window, with two trefoil panels under a quatrefoil, shields hanging from knots of foliage in the panels. Round the top of this tier runs a richly carved cornice, battlemented and pierced with crosses, and above this rise eight pinnacles supporting the lovely canopies of the second stage. In these canopies are three statues of Queen Eleanor holding her sceptre, all three original except for one head. Above the canopies rises the third tier of the cross, solid like the ground tier, carved like a lancet window and with rich finials on the six corner shafts. In the centre of these finials rises a daintily carved crown, from the heart of which springs a pinnacle topped with a stone cross.

This last bit seems to me to be a bit of a cheat on Mees part as Waltham Abbey and Waltham Cross are two distinct entities and the latter should, anyway, be properly covered in Hertfordshire (which it isn’t).

Flickr